Kim Duk-hyung Memorial Page

In the early hours of August 7th 1945, 8 days before the end of the war in the Pacific, a U.S. Army Air Corps B-24 'Liberator' bomber with eleven crew members on board, flew to destruction into the 3,000 foot peak of Mangwoon-san on Namhae Island in Southern Korea (Latitude: 34-20-00N, Longitude: 126-50-00E). All eleven airmen perished.

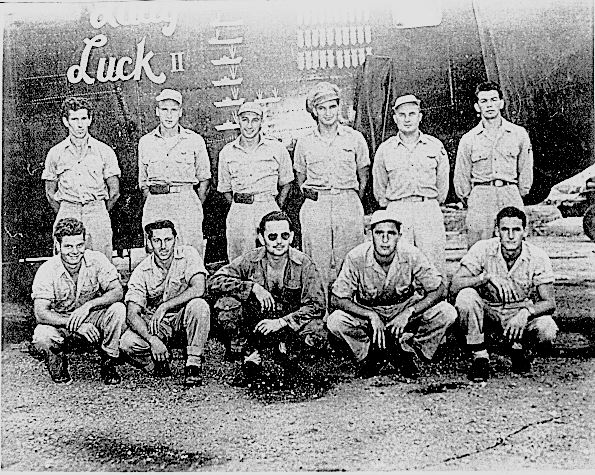

The crew of the B-24 that crashed on Namhae on 7 August 1945.

Back Row (left to right): Steve Wales, Nose gun; Ed Mills Jr., Pilot; Nick Simonich, Co-pilot; Joe Orenbuch, Navigator; Ron Johnson, Bombardier; Walter Hoover, Gun; Front Row (left to right): Jim Murray, Engineer; Henry Ruppert, Radar operator; Warren Tittsworth, Top gun; John Regnault, Radio operator; Tom Burnworth, Tail gun. |

Lt. Mills and his crew took off from Okinawa at 10:06pm on August 6th (the day of the atomic-bombing of Hiroshima) on an armored search for Japanese shipping off the southern coast of the Korean penninsula.

Hwa-do ( 화도 or 큰 관탈섬 ). Due to Hwa-do's relative isolation in the surrounding waters, and its jutting profile, the two B-24 Snoopers probably used this island as a sort of spot of radar certainty to fix their position and to serve as their "Initial Point" from which to begin their anti-shipping search.

|

The last contact with the ill-fated B-24 was made by VHF radio by Lt. Ellingson's plane at 1:50am on August 7th. Searches were conducted for the next few days (including one by Ellingson's crew on the morning of the 8th), with no sightings. The search for the lost plane was called off on September 9th, and the crew were officially listed as MIA.

|

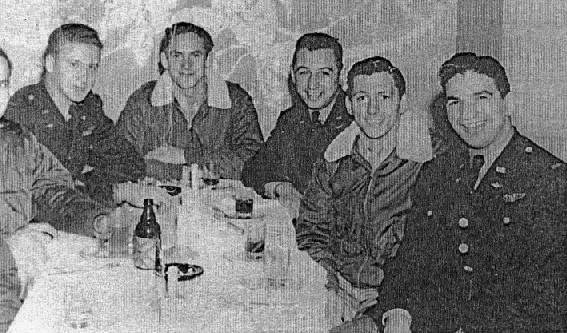

From left to right; Ed Mills, Nick Simonich, and Joe Orenbuch (the men in dress uniform).

|

Meanwhile, at the crash site on Namhae Island, Japanese authorities and Korean laborers searched the wreckage of the B-24 for useful parts, leaving the bodies of the crew to rot.

Kim Duk-hyung (circa 1950s).

|

After the war, Southern Korea was under U.S. Military Government occupation (1945-1948). It was during this time that the U.S military first learned the fate of the missing crew. US Army Captain Charles DeLaney was appointed military governor of Hadong, Sachon, and Namhae island, when he learned of the story of the American airmen while attempting to deal with the activities of Namhae's Red Peasant Union.

The monument that Mr. Kim built is situated below the peak of Mt. Mangwoon on Namhae Island.

|

The eleven airmen were to be the only U.S. casualties in Korea during the Second World War.

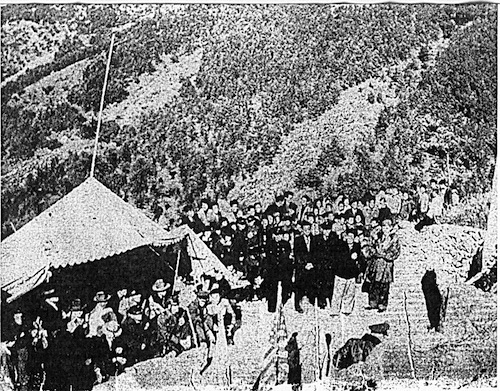

Back in Korea, Kim Duk-hyung resolved to build a memorial at the crash site for the airmen, who he believed had fought and died for freedom and justice against Japanese aggression. In 1948, Mr. Kim was granted Korean government approval to organize the "Memorial Activities Association for the U.S. Air Force". He raised enough money by 1956 to build a twelve-foot tall granite monument at the site on Mt. Mangwoon ( 망운산 ). This was done in spite of interruptions by communist partisans in the late 40's, and another dose of torture, this time at the hands of the North Korean army during the Korean Civil War. The monument dedication took place on November 30, 1956, and was attended by high-ranking South Korean and U.S. military and civilian officials. It has since been cared for by Mr. Kim, his family, and his supporters.

The gathering of dignitaries for the dedication of the monument, November 1956.

|

The monument as it looked in April 1996. The base of the monument is written in English, with the names of the airmen and the people involved in making the memorial. The front face of the monument's spire features Chinese calligraphy written by Korean president, Yi Seung-man (Syngman Rhee).

|

Me next to the monument. This gives you an idea of its size. On the right is Kim Duk-hyung and I standing in front of Mr. Kim's little pharmacy in Namhae city. The memorial hall is next door on the left. (April 1996).

|

Kim Duk-hyung receiving the Distinguished Civilian Service Award in 1986 (left). And (right) Co-pilot Nick Simonich's nephew presenting Mr. Kim with Nick's Purple Heart Award in 1997.

|

At the annual memorial service in 1997, US Army Captain Michael Fitzgerald, nephew of Co-Pilot Nick Simonich, presented Mr. Kim with Nick's Purple Heart as a gesture of their family's gratitude.

Veteran Arthur Frahm Remembers his Friend, Nick SimonichAuthor's Sidenote: In October 2000, the author of this site had placed a inquiry about the crew of this B-24 at an online forum dedicated to these aircraft (B-24.com). A former B-24 veteran named Arthur Frahm replied immediately. Mr. Frahm was a B-24 Co-Pilot who served in the war with Nick Simonich, Co-Pilot of the B-24 that was lost in Korea. This is what Mr. Frahm wrote: "Thank you for your E-mail of October 8th. The minute I saw your experience in Korea, and your connection with the 868th, I had a funny feeling in my stomach. You see, Nick Simonich and I were very close. He was my best friend. On August 6th, 1945, our squadron moved from a temporary base in the Philippines up to Okinawa. Our squadron was directly attached to the 13th Bomber Command (13th Air Force) with no Group or Wing. We flew up to Okinawa on the 6th and landed at Yontan Air Base. There was a strong crosswind on landing and we burned out a brake. After we had stowed our belongings in a tent Nick and I had dinner. They had been chosen to fly a mission that night and had already had their briefing before dinner. We generally ate all our meals together, if possible, so this evening did not break our routine. Nick and I talked about his mission and then he did a very strange thing: He asked me to hold his billfold, which neither of us had ever done, and he asked me to send it to his sister if anything happened to him! I tried to talk him out of keeping his billfold, but he wouldn't listen. We spent the rest of the evening together until it was time for him to report to operations, and then to the flight line. That's when we said goodbye. Nick and I had met at "snooper" training, and really hit it off. I, too, was the Co-pilot on the crew, so we had many things in common. We were transferred to Mather Field at Sacramento from Hamilton Field north of San Fransisco. We were to leave the United States from there. While waiting to leave, Nick and I decided it would be a good idea to rent a car and drive up to Donner Pass to ski. We hardly got on the slopes the next day when the lodge got a call from our crew to return immediately since we were to ship out that night. We made a hasty return (no interstate system yet) and were safe! Both our crews shipped out that night and we flew to Honolulu, arriving late the next morning. All the way across the Pacific, island hopping, we joined the 868th Squadron at Nooemfor. The squadron was in the process of moving to Morotai so we moved too. Nick and I built our tents on Morotai next to each other and continued our close association. On Morotai, I was certified as Aircraft Commander and flew a number of missions with our crew as pilot. On August 7th, we all were wondering if Nick and his crew had a successful mission and if they had returned. I had told the other officers on our crew about Nick's billfold and his premonition. We immediately started figuring out how much flying time remained with the load of fuel they were carrying. Soon most of the squadron officers were getting concerned about the Mills crew, with everyone calculating just how long they could remain airborne. After a while, we were all resigned to the fact that they were not going to return. Nick and I owned an Indian motorcycle together. When he didn't return, I sold it and sent half the money and his billfold to his sister. Approximately 15 years ago [mid 1980s] I was in touch with our Snooper [veterans] organization. They printed a small pamphlet type book relating to their organization, its members, and official accounts of missions. They printed an article about the Mills crew crashing on a mountainside in Korea, about the young man who buried the crew, his torture, and the monument and annual services. They confirmed his name [Kim Duk-hyung] and the fact that he was a druggist. That was the first I knew what happened to Nick and his crew. I apologize for rambling on, but he letter you sent and the information regarding the Mills crew, and Nick, really got my attention. Thank you so much. It means a lot to me." |

Kim Duk-hyung passed away on June 6, 2010 at the age of 95.

|

This author of this site owes a debt of gratitude to Mr. Bill Allen, brother-in-law of the late Lt. Ed Mills Jr. Mr. Allen's enormous help in providing me information about this story made this site possible.

Korea Photography Gallery