The Territorial Dispute Over Dokdo

Dokdo:

Dokdo's location and distance from nearest

landfalls.

|

The government of the Republic of Korea (South Korea) designated

Dokdo 'Natural Monument No. 336' in 1982. The government

generally does not allow private individuals to visit

the island, but as of early 2005, the Korean government is expected to further lift restrictions on civillian visits to the islets.

Dokdo consists of two tiny rocky islets surrounded by 33 smaller rocks. The Dokdo islets are located about 215 kilometers

off the eastern border of Korea and 90 kilometers east of

South Korea's Ullung Island. The islets are an

administative part of Ullung Island, North Kyongsang province, under the control of the Department of Ocean and Fisheries. Dokdo is also 157

kilometers northwest of Japan's Oki

Islands. Its exact position is 37° 14' 45" N and

131° 52' 30" E. Of the two Islets that make up Dokdo, Suhdo (the West islet) is a steep-sided rock about 100 meters high, while Dongdo (the East islet) is 174 meters high. The approximate total surface area of Dokdo is 0.186 square kilometers (56 acres).

Both rocks, about 200 meters distant, are the remains

of an ancient volcanic crater and are a refuge for Petrels and black-tailed

gulls and several, partly endemic plants.

Dokdo was first registered on charts in Europe after a French expedition under the leadership of Jean F.G. Perouse travelled to the East Sea/Sea of Japan in May of 1787, naming Ullung Island as "Dagelet", for a French astrologer, and Dokdo as "Boussole", after the name of one of the ships on the expedition. It was not until 1849, when French whale-hunters gave the name of their ship to the islets, that Dokdo began to be called "Liancourt Rocks". Other names have been ascribed to Dokdo ("Manalai and Olivutsa Rocks" by a Russian warship in 1854, and "Hornet Rocks" by the British, after one of their ships, the Hornet in 1855) but the name "Liancourt Rocks" is the only one of these names that is commonly seen on (usually older) English-language maps and sea charts published since 1910. The island was known to Koreans as "Kajido" (Sealion Island), "Sambongdo" (Three-Rock Island) and "Sokdo". Since at least 1881, the island has been called Dokdo by Koreans, meaning "Lonely Island" or "Rock Island", depending on the Sino-Korean character that one uses for the word, "Dok". Since at least 1905, the islets have been known by the Japanese name "Takeshima", but were previously known to Japanese as "Matsushima" or the "Rykano" islets.

Rival claims

Both Japan and Korea lay claim to Dokdo, and both

claim a long historical and geographical

connection with the islets.

The Japanese Claim

The Japanese assert that they had incorporated Dokdo, an island that they considered to be a terra nullius, into the Japanese Empire on February 22, 1905 when the Govenor of Shimane prefecture proclaimed the islets to be under the jurisdiction of the Oki Islands branch office of the Shimane prefectural government under the name "Takeshima", cited in Shimane prefectural proclamation number 40 of that year. This action by the Japanese government came about when, in September 1904, a Japanese fisherman from Okinoshima (Oki Island) named Yozaburo Nakai requested to be given exclusive rights to fish and hunt sealions in the area of Dokdo (Nakai later recounted that he initially believed the island to be Korean territory, and attempted to submit a request to the Government of Korea, but was dissuaded of this idea by the Japanese Fisheries Bureau Director, Maki Bokushin [...learn more about this in English and in Korean]). The fisherman also asked that he be given a ten-year lease of the island for sea lion hunting. Officials in the Japanese Government took Nakai´s request one step further and appealed to the government for the formal incorporation of the island. After having declared Dokdo (Takeshima) as a part of Imperial Japan in February 1905, Japanese officials entered the island´s name in the State Land Register for Okinokuni, District 4 on May 17th of that year.

This map is from the Japanese National Tourist Organization website, which obviously alludes to Japanese ownership of Dokdo by citing ´Takeshima´ with Oki Island.

|

Who Was Nakai Yozaburo?

Korean: ��ī�� ���ںηδ� ��������?

On June 5th, Yozaburo Nakai´s request came through when he and three others were given permission by the Shimane prefectural government to hunt sea lions at Dokdo. In the year that followed, the prefectural government posted a territorial sign and conducted inspections and surveys of Dokdo. On April 24, 1939, a decision to incorporate the island under the jurisdiction of Goka Village was made by the Goka Village Assembly on Oki Island, Shimane Prefecture. Imperial Japan had also made use of Dokdo in a military capacity, when they named the islets "Maizaru" Naval Station on August 17, 1940, restricting the island to purely military uses.

With Japan´s defeat in the Pacific War in 1945, the victorious Allied Powers renounced the Japanese claim to Dokdo. Under U.S. military occupation (1945-1952), the highest governmental authority in Japan was the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP), which delimited Japanese administrative territory. SCAP´s first major opinion concerning the territory of postwar Japan was cited in an instruction SCAP gave to the Government of Occupied Japan.

The order, SCAPIN (SCAP instruction) #677 of January 29, 1946 specifically outlined

Japanese territory and stated that the islands

disputed between Japan and Korea-

Utsuryo Island (Ullungdo), Liancourt Rocks (Dokdo),

and Quelpart Island (Chejudo) were to

be excluded from Japan's administrative authority.

However, to SCAPIN 677 was added this

caveat: "nothing in this directive shall be construed

as an indication of Allied policy

relating to the ultimate determination of the minor

islands referred to in Article 8 of the

Potsdam Declaration." Dokdo´s exclusion from Japan remained SCAP policy throughout the occupation, (another instruction, SCAPIN 1033 of June 22, 1946, prohibited Japanese nationals from approaching within 12 miles of Dokdo). With Dokdo´s territorial status yet to be determined by a peace treaty between Japan and the allied powers, U.S. authorities in Japan decided to use the island as a bombing range. Dokdo was the second island bombing range established in Korean territorial waters; the first being the Kimpo Air Base Air to Ground Range on the West Coast of Korea on the island of Kochumdo, just 7 kilometers north of Incheon.

In June 1947, the Japanese Foreign Ministry appealed to the U.S. occupation authorities over Japan's claim to sovereignty over both Ullungdo and Dokdo in a treatise entitled, "Minor Islands in the Sea of Japan", hoping to influence U.S. opinion in any future deliberations concerning the island that would take place in the upcoming peace treaty negotiations. The Japanese ministers denied Korea's ownership on the grounds that "no Korean name exists for the island" and that Dokdo "is not shown on the maps made in Korea". The Japanese document also argued that the settlers on the island had just arrived recently and that the island´s development was "still in an incipient stage", and because of this, it was not within the Korean government´s ability to develop the island.

The location of Dokdo

in relation to Korea and Japan.

|

The Japanese efforts to regain Dokdo during the negotiations of the peace treaty eventually failed.

Although the provisions in Article 2(a) of the 1952 San Francisco Peace Treaty between

Japan and the former allied powers settled sovereignty

over the islands of Ullungdo, Kommundo, and Chejudo (all to Korea), the ownership of Dokdo was not settled in the treaty.

The reasons for the omission of Dokdo´s sovereignty from the treaty are many. In the process of negotiating, writing, and rewriting the treaty, the first five and seventh drafts of the treaty (written betweeen 1947 and 1949) actually provided that Liancourt Rocks (Dokdo) be given to Korea by including the islets in the Article 2(a) list of territories to be recognized as Korea´s. This initial inclusion of Dokdo in the Article 2(a) list was consistent with previous Occupation policy. Unfortunately for Korea, the American authorities who made the decisions to exclude Japanese sovereignty over Dokdo at the beginning of the occupation (the SCAP Headquarters Government Section), were not the same Americans involved in drafting the territorial sovereignty provisions in the final drafts of the San Francisco Peace Treaty.

Instead, American judgements on these issues were largely governed by those in the Diplomatic Section of SCAP, led by a great American friend of the Japanese Foreign Ministry, William Sebald. As Acting Political Advisor in Japan (essentially General MacArthur´s acting "Foreign Minister"), Sebald´s long involvement in Japan and strong personal connections with Japanese officials influenced his opinions towards the ownership of Dokdo, evident in his communications to the US State Department. Sebald´s influence and possible US military considerations eventuated the removal of Dokdo from the Article 2(a) list by November 1949. Mirroring Imperial Japan´s actions in 1904-1905, American planners are known to have considered Dokdo´s military value as a weather and radar station around this time. This came about as MacArthur requested that the treaty be used to establish joint US-Japan trusteeships of strategic land in and around Japan, so as to use these territories to defend Japan from the Soviet Union. Therefore, evidence suggests that historical title was perhaps not the grounds for allied decisions in the disposition of territories in the treay. In fact, it was thinking like this that later led some in the Allied Powers, during the exigencies of the Korean War, to toy with the idea of using the treaty to cede Cheju Island to Japanese sovereignty so that the island would not fall into the hands of the Communists.

Another very important reason why Dokdo´s sovereignty was left unanswered by the peace treaty was that the president of the Republic of Korea (ROK), Yi Seung-man (Syngman Rhee) did not effectively focus his government´s attention on the ownership of Dokdo when negotiating with U.S. authorities over Korea´s territorial concerns. The Korean president instead focused on an unrealistic demand for Korean sovereignty over Tsushima Island (as a form of war reparations from Japan, an idea which the drafters of the treaty never seriously entertained). Much of his attention was also focused on suppressing domestic political rivals than with maintaining his country´s territory. In fact, the Rhee government never bothered to produce a scholarly, well-documented study of the Korean historical record on Dokdo that could offer the American drafters of the peace treaty an alternative to the Japanese Foreign Ministry´s monograph, "Minor Islands in the Sea of Japan". The ROK only produced a thorough study on Dokdo in the Summer of 1953, long after the San Francisco Peace Treaty had gone into effect.

Even after the peace treaty was signed and talks on the normalization of relations between the ROK and Japan were underway, the Korean demand for recognition of their country´s sovereignty over Dokdo continued. This was particularly the case after the Korean president announced the establishment of a territorial line (sometimes called the Rhee-Line, or Peace Line) in the East Sea/Sea of Japan on January 18, 1952, that encompassed Dokdo on Korea´s side of this line. Another development that heightened the Dokdo issue in the minds of the Korean public was when a bombing incident at Dokdo on September 15, 1952 had raised awareness in Korea over the impending fate of the island. The growing demand from Korea placed U.S. authorities in the region in the undesirable situation in which the U.S. would have had to pick sides in a territorial dispute between Korea and Japan, whose cooperation with the U.S. and each other, was important to U.S. strategic designs. The documentary record shows that the Americans increasingly attempted to distance themselves from the dispute.

See also: U.S. Diplomatic and Military History of Dokdo (1945-1952)

What the American Military Occupation of Japan and Korea might mean for the sovereignty of Dokdo

Dr. Pyun Yung-tai, Foreign Minister of the Republic of Korea from 1951-1955.

|

The only ROK high-official that tried to effectively campaign for Korea´s claim to Dokdo before the peace treaty went into effect was the Foreign Minister, Pyun Yung-tai, who argued for Korean ownership of the islets based largely on allied policies and the decisions made by SCAP immediately after the Pacific War, in particular, SCAPIN 677. Dr. Pyun argued that SCAPIN 677 separated Dokdo from Japanese territory until a time which the Allied Powers could enact another positive decision to retrocede Dokdo to Japan. He believed that since this never took place, and that the San Fransisco Peace Treaty had no positive provision to retain Dokdo within Japanese territory, the peace treaty should be construed to have affected Dokdo´s permanent separation from Japan. If it hadn´t been for Dr. Pyun´s efforts, Korea´s stand on Dokdo might never have been understood by influential U.S. officials, since other Korean arguments for sovereignty over the island were neither clear nor consistent during this period. In the end, however, the ownership of Dokdo was considered too contentious to handle, and it was left out of the final draft of the peace treaty. Thus, the failure of the San Francisco Peace Treaty to resolve the legal ownership of Dokdo is a major reason why the rivalry over the island continues between Japan and Korea.

Years later in 1966, the Japanese Foreign Ministry produced an extensive study on the history of the island. This study, Takeshima no rekishi chirigakuteki kenkyu (An Historical and Geographical Study of Takeshima), was authored by a Foreign Ministry researcher by the name of Kawakami Kenzo. The Foreign Ministry of Japan has since used Kawakami´s research as the Government of Japan´s basis for its claim to sovereignty over Dokdo. Kawakami attempted to show that Koreans were not aware of the existence of the island. He asserted that the island that Koreans cite in their Choson Dynasty (1392-1910) documents as Dokdo simply does not exist. He also states that Dokdo is not visible from Ullungdo and that Koreans did not have adequate navigation skills (until the late 1800s, when Japanese people taught the Koreans proper sea navigation) to reach Dokdo by boat, and therefore Koreans could not possibly have been aware of the island. This is a very interesting assertion, since Koreans travelled by boat from all points on Korea´s east coast to Ullung Island, but (according to Kawakami) somehow could not make the much shorter trip from Ullungdo to Dokdo.

Based on the above precedents, Japan still declares Dokdo

to be within its territorial

boundaries. The Japanese still consider their 1905 incorporation of Dokdo into the Japanese territorial sphere as legally binding. The 1905 claim is probably the Japanese Foreign Ministry's most solid claim to Dokdo. However, it is as if they no longer care for it. They also believe that previous opinions of occupation authorities were made null and void by the 1952 peace treaty. Since 1954, the government of Japan has been inviting the Koreans to take the issue before the International Court of Justice. The Koreans have consistently refused, stating that Dokdo is not a disputed territory, but simply Korean territory.

To this day Dokdo is on Japanese registers as a part of Goka Village, Oki-gun, Shimane Prefecture. The Japanese government has even allowed their citizens to declare themselves

residents of the islets.

See also: Why won't the Koreans agree to take the Dokdo issue before the International Court of Justice?

The Korean Claim

The Koreans, however, lay their claim to Dokdo based

on earlier and more numerous

precedents than Japan. They point to the document that

named it as a territory that was first

incorporated into the Korean Shilla Dynasty in 512

AD. They also point to various government and military reports, policy decisions, land surveys, and maps that were drawn in later centuries that do, in fact, show Dokdo (in its accurate geographic position) to be Korean territory. Some of these documents were even published in Japan: Japanese cartographer Dabuchi Tomohiko cited Dokdo as Korean territory in "Kankoku Shinchishi (New Geography of Korea), Teikoku Encyclopedia Number 134", published in September 1905; six months after the islets were "incorporated" into Shimane Prefecture. In a survey of Korea that was requested by the Colonial Government, Ihohara Fumiichi referred to Dokdo as belonging to Korea. In a 1930 article, Japanese scholar Hibata Sekko mentioned that Dokdo belonged to Kangwon Province, Korea. The Japanese Navy had also cited Dokdo as an appended island to Ullungdo, and Korean territory, in its 1923 publication, "Chosen Engan Suiroshi" (Korean Coastal Straits), as did Japanese maps published in 1872, 1877, and 1936.

See also: Mapping Confusion regarding Dokdo

Koreans also complain that the

Japanese took advantage of Korea's

political weakness vis-a-vis Japan in 1905, when the

islets were registered as a part of

Shimane prefecture, Japan. Koreans rightfully argue

that Korea had not been able to effectively protest

the Japanese action at the time because Japan had had

already taken control of the foreign

affairs of Korea via the Protectorate Treaty of 1905, also known as the "Eulsa Treaty" or the "Second Japan-Korea Agreement". (The ratification of the treaty itself had been forced on Korea by the Japanese delegation to the treaty "negotiations" led by Ito Hirobumi and General Hasegawa Gonnosuke, with no signatures given by either the King or the Prime Minister of Korea.) The Korean side also points out that the Japanese did not inform the Korean Government of their claim until 1906, and then only indirectly. Upon learning of Japan´s decision, Korean officials in 1906, at both local and national levels, did in fact recognize and document the Japanese action as a violation of Korean sovereignty. However, due to the loss their nation´s independence and foreign affairs capability, no action was taken. Currently, the Japanese Foreign Ministry website states that it was not necessary for Japan to inform other countries of this territorial acquisition, although international precedents and the majority view of scholars consider notification to be indeed necessary. The Japanese themselves evidently thought that notification was necessary when it acquired the Bonin (Ogasawa) Islands in the Pacific: Then Japan contacted Great Britain and the U.S. several times, which were only remotely involved in them, and it notified 12 European countries of its establishment of control over these islands.

To bolster their claim to Dokdo, Koreans also point to the opinions SCAP rendered on no less than three occasions during the occupation that excluded Dokdo from Japanese control.

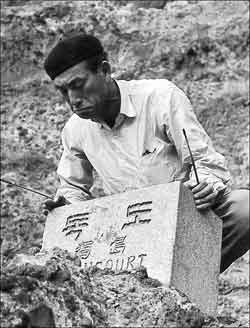

This photo clearly calls into question the argument made by Kawakami Kenzo that Koreans on Ullung Island, ´were not aware of the existence of Dokdo since the island could not be seen from Ullungdo due to the thick vegetation there.´.

|

Koreans have also pointed out the falsehoods in the Japanese Foreign Ministry-sponsored 1966 study by Kawakami Kenzo. Kawakami´s disparagement of Korean Choson Dynasty documentation has been shown to be baseless. Futhermore, Kawakami´s claim that Dokdo was not (is not) visible to Korean eyes on Ullungdo is also a falsehood, since Dokdo is visible at a height of 120 meters or higher in elevation from Ullungdo, an island with a maximum elevation of 985 meters.

Japanese have also made claims that Japan´s "effective management" of Dokdo had been in place as early as the 17th Century, when the Japanese merchant families Otani and Murakawa obtained permission from the Japanese Government to travel to Ullungdo. Not only was Japan´s "effective management" of Dokdo highly improbable at this time (the merchant families were interested in exploiting Ullungdo, not Dokdo), it also creates a contradiction in the Japanese claim. In 1905, the Japanese recognized the islets as a terra nullius, and therefore ownerless (never having been managed) before that time. These contradictory Japanese claims under international law have never been fully addressed by official or unofficial sources in Japan. Probably as a result of this contradiction, the Japanese Foreign Ministry's Takeshima brochure no longer mentions the fact that Japan incorporated Dokdo as a terra nullius. The change in the wording of the Foreign Ministry´s webpage reflects the official shift in Japan´s claim from "acquisition by prior occupation" to a claim that Dokdo was an "inherent territory". It is quite a nonsensical shift, as it can be proven false by simply studying the Ministry´s own maps and documents that range from the 17th Century to the Meiji Era to just a few years before the 1905 annexation. The Takeshima Incident of 1837 is a particularly instructive example of Japanese views regarding Dokdo prior to 1905.

The Text of Imperial Ordinance No. 41 (Article 2), from October 25, 1900. The Japanese Foreign Ministry website very conveniently dismisses this document, which was enacted at least four years before Japan claimed to have "incorporated" Dokdo.

|

Yet another problematic issue for the Japanese claim to Dokdo, particularly Japan´s 1905 ´incorporation´, is the existence of a land survey conducted by Korean authorities in 1900, known as Korean Government Imperial Ordinance No. 41 (Article 2), which stipulated that the Ullungdo-kun office was to have jurisdiction over Sokdo (Dokdo). This Korean Government order was promulgated on October 25, 1900; over four whole years before Japan claimed the island as a terra nullius. Japanese critics of this ordinance assert that the island named in the document, Sokdo (in Sino-Korean characters), is not Dokdo, but refers to the island, Jukdo (also known as Kwanumdo); an island that is almost penninsular in appearance and in the far Northeastern corner of Ullungdo. The evidence by which they conclude that Sokdo is Kwanumdo has not been fully qualified. It is difficult to believe that Sokdo is Kwanumdo, based on Kwanumdo´s history, appearance and topography, and as "Dokdo" and "Sokdo" essentially mean the same thing: "rock island". As the text of the ordinance was written in Sino-Korean (Chinese) characters, the name appears as "Sok", and not the dialectal pure Korean, "Dok" (See similar dialectal transformations).

Other critics often go further in the past to cite old Chosun maps that do not accurately position islands (the 1834 Chosun map or Daehanjiji). These maps show Ullungdo much closer to the Korean penninsula and Dokdo in an inaccurate position. These critics then fill in the blanks with their own interpretations to claim that when these maps similarly show "Usando", it is in reference to Jukdo or Kwanumdo, not Dokdo. They fail to mention the fact that Chosun cartographers would often place islands closer to their home territory to denote ownership, not to denote accurate positioning in the ocean. What also is missing in their arguments are the contemporary documents to these maps, both Japanese and Korean, that state clearly: "Usando is what Japanese call Matsushima..." (Matsushima was the original Japanese name for Dokdo). These critics put more importance on their own loose interpretations of geographically-inaccurate maps than on clearly-worded documents.

See also: "New Dokdo Theory" by Sam Ahn.

Historical Context: 1870s-1905

Therefore, despite the seemingly "legal" aspects of Japan´s incorporation of Dokdo into the metropolitan area of Japan, the Japanese action must be seen from an historical point of view. It must be remembered that Dokdo was annexed together with the rest of Korea, when Japan extended its Empire over the former Korean state in the period, 1900-1910. Japan´s ´acquistion´ of Dokdo resulted from an overall increase in Japanese aggression in Korea in the late 1800s, when Japan began to openly acquire monetary rights, railway, mining, and fishing concessions in Korea, in addition to conducting outright invasions of Korea´s outlying islands. At first, when Japanese civilians began exploiting Korean islands like Ullungdo in the late 1800s, the Japanese Government acquiesed to Korean Government complaints and removed Japanese civilians who were illegally fishing and logging. The Japanese Dajokan, the Council of State, even ruled in 1877 that "our country has nothing to do with" Ullungdo and Dokdo .

However, the Japanese position changed after the Sino-Japanese (1894-1895) and Russo-Japanese (1904-1905) Wars, when these Japanese victories boosted Japan´s willingness and power to control the areas just outside of territorial Japan. The Korean islands in this area of the East Sea/Sea of Japan (Kommundo, Chejudo, Ullungdo and Dokdo) were seen to have value to the Japanese military in the Russo-Japanese War, and the Japanese military essentially invaded these sovereign Korean territories to establish watchtowers and to link them via submarine telegraph cables.

A Japanese Naval map from 1905 that details the underwater telegraph sytems in the sea space between Korea and Japan. This map details how Japan occupied Korean minor islands for miltary reasons.

|

It was also during this war with Russia that the Japanese public began to become aware of Dokdo, since many of the naval battles between the Russian and Japanese fleets took place in the area of Ullungdo and Dokdo. Previously illegal Japanese civilian encroachment in this sea area (and indeed the rest of the Korean peninnsula) was encouraged by the Japanese Government in this period. It was in this milieu of Japanese imperialist advance into Korea that Nakai Yozaburo approached the Japanese Government to secure exclusive rights to Dokdo, resulting in the Japanese acquisition of the islets.

Therefore, the Japanese incorporation of Dokdo into Shimane Prefecture was intimately connected to, and a result of, Japan´s imperialist aggression in the early 20th Century. However, the Foreign Ministry of Japan still clings to its belief that the territories it acquired in the period of 1894-1910 were "internationally recognized", and therefore were acquired validly. It is quite curious that Japan continues to hold onto a claim of territorial sovereignty that was enacted at a time when Japan was engaged in imperial expansion.

A final thought on this issue...

The Cairo Conference of 1943 stipulated that "Japan will be expelled from all territories which she has taken by violence and greed [since the time of the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95]." Considering Japan´s methods, there can be little doubt that Japan´s annexation of Dokdo in 1905 (along with all other Korean territories by 1910) falls within the definition of territories taken by greed, as defined by the Cairo Declaration. If Japan believes that its methods in acquiring Dokdo in 1905 were legitimate, then Japan must believe that it can still, by the same logic, claim sovereignty over the rest of the Korean Peninnsula...

Conflicts in the 1950s

In the 1950's, South Korea took active measures to

stake its claim. The first was in September 1952, when then president Yi Seung-man (Syngman Rhee) sent a research vessel to Dokdo (resulting in the aforementioned bombing incident), causing the territorial dispute to capture the public's attention in Korea and Japan for the first time.

Koreans made it clear that Dokdo was theirs in the 1950s.

|

The conflict over dokdo escalated considerably in 1953 and 1954, beginning with ROK president Syngman Rhee´s establishment of the "Peace Line" or "Rhee Line" on January 18, 1952, in which South Korea placed a territorial boundary line that extended out into the East Sea/Sea of Japan to encompass Dokdo: Much to the chagrin of the Japanese Foreign Ministry. Over the next two years, Japanese patrol vessels would approach within close distance of the island and attempt to, and sometimes actually land on the island. These patrols would provoke reactions from the Korean volunteer coast guards, who kept watch over Dokdo since being stationed there on April 20, 1953 and led by Korean War hero, Hong Soon-chil. In an incident on June 27, 1953 crews of two Japanese coast guard vessels, led by Tomizo Sawa and Nobuo Igawa, drove six of the Korean coast guards from their base on the East Islet to the West Islet, landed on the island, and erected a Japanese territorial marker on the shore. This action had little effect in Korea, since most of the government´s focus was on events concerning the end of the Korean War. However, it was not forgotten by the president of Korea, when a year later, he sent a letter to North Gyeongsang Province police chief Kim Jong-won, promising him a shipment of mortars and 100 rounds of mortar bombs for the Dokdo coast guards so that the weapons could be used to "scare off" intruding Japanese ships. When issuing the orders, however, the provincial police chief changed the wording of the president´s orders from allowing the coast guards to "scare off" Japanese ships, to allowing them to "sink" Japanese ships.

;

Korean coast guards stationed at Dokdo in the 1950s. They maintained the Republic of Korea´s control over the islets, and engaged any Japanese vessels that entered the surrounding waters.

|

On July 12, 1953, three Japanese patrol boats (two of which were named the ´Hekura-ho´ and ´Oki-ho´) arrived to stage their typical show of force. Upon arriving at Dokdo, the Japanese ships came under mortar fire from the Korean forces on Dokdo. The ships returned fire, but the Japanese lost one boat and suffered 16 casualties. Yet another such incident occurred on August 24, 1954.

The Japanese Foreign Ministry angrily denounced the Korean "illegal actions" in a letter to Seoul on November 30th. The Japanese demanded an official apology from the ROK and the removal of the Korean coast guard from the island. The Koreans did not give in. It was at this time that Japanese right-wing groups discussed plans to assemble an armed reaction force in an effort to "free Takeshima" from the Koreans. In the end, this incident only really served to heighten the animosities felt by either side and undoubtedly slowed down rapprochement between Korea and Japan.

In 1954, the Koreans had also built a concrete

lighthouse and building, and a helicopter landing pad

on the East Islet The islets have remained under the protection of Korean maritime guards ever since.

Despite these setbacks for their claim, Japan has officially declared

several times since 1949 that

Dokdo is a part of Japan, with South Korea protesting

against this territorial claim time after time.

Dokdo in the 1965 R.O.K./Japan Basic Relations Treaty

Korean Foreign Minister Lee Dong-won (left) and the Japanese Foreign Minister, Etsusaburo Shiina reviewing ROK troops at Kimpo Airport upon Shiina´s arrival in Korea to negotiate the 1965 Normalisation Treaty between the ROK and Japan.

|

The dispute over Dokdo

hindered the normalization of diplomatic

relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea (R.O.K.) from the end of the Pacific War in 1945, to June 1965 when the Basic Relations Treaty was signed between Japan and the R.O.K.

As with the 1952 San Francisco Peace Treaty, sovereignty over Dokdo was deliberately left out of the eventual text of the treaty upon request of the Korean side. Nevertheless, Dokdo was discussed in conversations between ROK Foreign Minister Lee Dong-won and Japanese Foreign Minister Etsusaburo Shiina. The normalization of relations with Japan was not popular among the Korean public, who demanded a definite territorial boundary between Korea and Japan

(known as the ´peace line´, or ´Rhee line´), war reparations from Japan, and ownership of Dokdo on Korea's side of the peace line. Therefore, even the treaty of 1965

did not resolve the ownership of Dokdo between the two nations.

The American position regarding Dokdo (although it might have vacillated between Korea and Japan in the past) is essentially one of "non-recognition" of both Korea´s and Japan´s claims to sovereignty over the islets. This American attitude towards Dokdo first emerged in 1953, when U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles stated that the "US view re Takeshima [is] simply that of one of many signatories [out of 47 other nations] to [the San Francisco Peace] treaty." As the territory of South Korea was secured at the end of the Korean War, the United States felt no need to keep any ostensible support for Japan´s claim to Dokdo (although the official US opinion concerning Japan´s ownership over Dokdo was kept secret even from the Japanese themselves). Dokdo and Cheju Island were no longer in danger of falling into the hands of the North Koreans, and William Sebald´s proposed weather and radar stations at Dokdo were no longer needed. This "non-recognition" of any nation´s claim to Dokdo has also been in place since at least 1954, as the U.S. has maintained defense pacts with both the Republic of Korea and Japan. In the Japanese case, the U.S. takes into account the fact that the Japanese do not control the islands, thus placing them outside the territory governed by the Japan-U.S. Mutual Security Treaty. In regard to Korea´s claim, it is unlikely that the U.S. would recognize Korea´s claim to the island based on the known history of the dispute. As such, the Mutual Defense Treaty between the U.S. and the ROK would also appear to be inapplicable since the treaty commits the U.S. to defend only that territory recognized by the U.S. as belonging to Seoul.

In an interesting sidenote, however, an unconfirmed story has emerged alleging that a United States Army helicopter crew stationed at Pyongtaek, Korea were involved (unwittingly) in Korean efforts to have the first Republic of Korea citizen born at Dokdo in 1989. Supposedly coordinated by the ROK Navy, American aviators piloting a UH-60 helicopter were requested to ferry an expectant mother from Ullungdo to Dokdo, where she gave birth ten hours after landing there.

Right-wing groups in Japan protest against Korean policy regarding Dokdo.

|

Recent Conflicts

The most

serious recent row over the Islets came in February 1996 when

Japanese Foreign Minister Yukihiko Ikeda publicly

reaffirmed Japan's territorial claim to the

islets after South Korea made

plans to build a wharf on them. Certain Japanese

ministry officials such as Ikeda, Miyaki and others

occasionally make such statements in order to garnish

more popularity among Japanese voters by sounding

'tough', regardless of how such behavior upsets

neighboring countries. In this case, the Korean

defense ministry had had decided

to cancel that year's spring military maneuvers near

Dokdo to avoid political friction, but

changed back to their original plans after Ikeda made

his statement.

Some time later, the Japanese "self-defense" forces

conducted exercises in the same ocean that were meant

to practice

the re-occupation of an island. Japan then later

renamed the military drill a `landing exercise' for

fear of an overly

negative reaction from Korea. To Koreans,

there was little doubt about what the Japanese forces

were really practicing.

There has also been the constant controversy over Japan´s refusal to acknowledge the full history of the sovereignty dispute over Dokdo (in addition to other issues) in history textbooks published for Japanese high schools. In April 2002, the Japanese Ministry of Culture and Science approved texts from the book publishing companies, Meiseisha and Jitkyosha, that question the Korean claim to Dokdo without even attempting to explain the Korean argument. There is also scant nuance in the Korean views of the issue.

Energy Resources and Exclusive Economic Zones

The Korean flag flies

at Dokdo. The Chinese characters declare Dokdo to be

Korean land.

|

The Dokdo issue is not just

about the ownership of the two islets.

Both countries consider the ownership of Dokdo as an

anchor for their respective interests in the

surrounding waters.

At stake are claims to about 16,600 square nautical

miles of sea and seabed, including areas that

may hold some 600 million tons of gas hydrate (natural gas condensed into semisolid form). This gas hydrate is believed to be deposited along the broad seabed extending from Dokdo to Guryongpo, North Kyongsang Province. Gas hydrate is a next-generation energy source that could be made into liquid natural gas if adequate technology is made available. The island is

surrounded by fertile fishing grounds, and both sides

frequently attempt to bolster their claims to it.

Also spurring the fishing competition is a fear of

dwindling sea resources. Japanese fishing officials

say the depletion of fish stocks in other parts

of the world means their country must rely more on

waters closer to home.

The northwestern Pacific in general has more underused

fish stocks than other areas,

according to the U.N.

Today, few marine areas in East

Asia remain unclaimed-and many claims overlap.

The global Law of the Sea Convention, which entered

into force

in November 1994 after more than 20 years of

negotiation,

embodies most international law and state practice

relating to

the oceans.

Under the treaty, every nation with a seacoast is

entitled to exercise

jurisdiction over resources and certain activities in

waters extending

as much as 200 nautical miles from a coastal

baseline-an Exclusive

Economic Zone (EEZ).

The problems here lie in the details,

and this is nowhere better illustrated than in the Law

of the

Sea Convention, in which the extent and degree of

jurisdiction

a nation exercises is determined by a host of arcane

factors,

including the drawing of baselines, distance from the

coast, and the

meaning of "continental shelf," "equidistant lines,"

and the like.

According to the convention, a

nation can claim sovereign rights over resources and

all related

activities, as well as jurisdiction over artificial

structures, scientific research, and protection and

preservation of the

marine environment, within its 200-nautical-mile

Exclusive Economic

Zone (EEZ).

But because tiny islets that are only flyspecks on a

map may be

used as a basis to claim an Exclusive Economic Zone,

many maritime

disputes focus on the ownership of tiny

islands, reefs, and other "features" such as

Dokdo, the Diaoyu islands in

the East China Sea, and the Spratly/Xisha Islands in

the

South China Sea. Unfortunately, the convention

offers little specific

guidance for the settlement of boundary disputes.

Thus nations may still feel a need to engage in

provocative military

posturing, and the possibility of military conflict

remains.

The 1996 dispute over Dokdo only further

stressed the

already fragile relations between South Korea and

Japan.

Nonetheless, ways have been found to

deal with boundary uncertainty. Under a

joint-development approach,

these countries agree on the extent of the area in

dispute, set

aside the actual boundary question, and reach

agreement on joint

exploration and exploitation of hydrocarbons.

This strategy is supported by the Law of the Sea

Convention, which

stipulates that, pending agreement on the delineation

of the

continental shelf or the boundaries of Exclusive

Economic Zones (EEZs),

states should try to enter into provisional

arrangements.

Perhaps the strongest reason for a state to opt for a

joint undertaking is

to protect its interests in potential oil or gas

deposits,

combined with a desire to maintain good relations

with the other state.

Joint development is an idea that may look

increasingly attractive as the need for oil

intensifies.

Japan and South Korea have taken such an approach, and

have

established 230-mile EEZs under the U.N.

Convention on the Law of the Sea. After years of

negotiation, the

two countries signed the treaty in July 1996, setting

quotas and regulations in

each other's zones.

The resolution of the dispute over Dokdo is still

uncertain. Despite the agreement the two countries

entered into in 1996, Japanese officials still make

remarks that anger people in Korea, and Korean voices

are getting increasingly indignant over the issue.

However, governments

outside of Japan and Korea really have no interest in

getting involved in the issue. In cases like this,

possession is nine-tenths of the law. Therefore, Dokdo will

probably remain in Korean hands; That is unless the

Right Wing in Japan takes over and/or the Japanese

pacifist constitution is rewritten to accommodate a

Japanese military take-over of the Islets.

To conclude, a quote from one of the contributors to the Guestbook is quite appropriate:

"...a war over Dokdo would be insane for both countries involved, and Japan in particular (because given the situation on the ground, it would have to start it). Which means if rational decision making is in play, this issue will be solved when one of the two -- probably Japan -- finally decides to throw in the towel. Until that time, this issue will continue to [hinder] bilateral relations until people in Tokyo decide to get smart and cut their losses."

Recommended Reading:

"Japan's Incorporation of Takeshima into Its Territory in 1905", by Kazuo Hori, in the English-language journal, KOREA OBSERVER, Vol. XXVIII, No. 3, Autumn 1997.

(Originally published in Japanese in Chosenshi kenkyukai ronbunshu "A Collection of Articles on Korean History", No. 24, Tokyo, 1987)

Recommended Reading on the Internet:

This informative site on the history of Dokdo´s sovereignty (www.dokdo-takeshima.com)

Here´s a new article on Dokdo at Citizendium.

An Overall History of Dokdo

by Professor Shin Yong-ha of Seoul National University

Resolution of the Dokdo Island Dispute(The authors argue that Dokdo is still US Military "property", and that the interested parties should appeal to the US Congress)

-by Richard W. Hartzell and Roger C. S. Lin

"Japan´s Position on Takeshima" -from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan

A Takeshima blog operated by Gerry Beavers

|

Sign Guestbook

This research compiled by Mark S. Lovmo